- Home

- Beyers de Vos

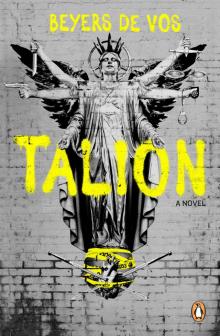

Talion Page 9

Talion Read online

Page 9

‘And on the night, you weren’t with her?’ she asks.

‘No, I was out with friends. She never invited me to those Friday-night things with her brother. They were, like, sacrosanct or something.’

‘What were you talking about on the phone?’

‘We were maybe going to meet up afterwards. After she finished. We were planning that when . . .’

‘Did you hear the gunshot?’

‘Yes.’ He swallows the last bite of his cornflakes loudly. ‘And then the phone went dead.’

‘Did you do anything?’

‘I tried to phone her back a few times.’ He shrugs.

‘You weren’t worried?’

‘I didn’t think . . . I mean, she said they were there. At the bar. I didn’t think it had anything to do with her. The shot. I thought she would phone me back when she had a moment.’

‘And when she didn’t?’

He shrugs again. When Nolwazi doesn’t say anything to this, he continues: ‘Look, she was sweet and cute, but it wasn’t like we were serious or anything. Just having fun. I knew her brother better than I knew her.’

‘You did?’

‘Yup, he’s the one who introduced me to Freya.’

‘You didn’t tell the officer who took your original statement that.’

He shrugs, and says, ‘He didn’t ask. And I didn’t think it was important. Was it?’

‘Could be.’

‘How?’

Nolwazi ignores this and asks instead, ‘And how did you know Ben?’

‘He was friends with my roommate, Leo.’

‘Is Leo here?’

‘Sure. Yo, Leo? Could you come on out here for a sec?’ he calls in the general direction of the bedrooms. A young man comes out a moment later, shirtless and groggy.

‘Man, I was fucking sleeping—’ But he stops when he sees Nolwazi. His eyes grow wide and he freezes suddenly, awkwardly. ‘Who are you?’ he says.

‘Inspector Nolwazi Mngadi. I am here to ask a few questions about the murder of Benjamin Rust. Eric here says you knew him?’

Leo visibly relaxes: his shoulders drop; his brow unfurls. Even his tattoo, a tree growing out from under the waistband of his pants, seems to expand as his stomach relaxes. ‘Oh, that. Took you long enough,’ he says. ‘Yes, I knew Ben.’

Nolwazi watches as Leo moves into the kitchen and takes a seat next to Eric. ‘How long have you two been roommates?’

‘Two years.’

‘And how did you meet Ben . . . er, Leo?’

‘On campus, you know, mutual friends. Class.’

‘You were studying the same thing?’

‘No, but we both took English.’ Leo pauses, then asks, ‘Is he buried anywhere?’

‘You’ll have to ask his sister that.’

‘I have. She hasn’t been replying to my messages. I don’t even know if there was a funeral.’ Leo gets up from his chair and busies himself with the kettle, turning his back on her. Nolwazi doesn’t know what to say to that. She takes a minute to look around the flat before having to ask the predictable but necessary question. Before she can push it out, Leo interrupts her: ‘Why did it take you so long to come and speak to us? Why didn’t you come right after he died?’

‘We did take a statement from Eric. We didn’t realise you knew him; we didn’t even know that you existed.’

‘Yeah, you and lots of people.’

‘And,’ she continues, defensive, ‘we were following other leads.’

‘But you still haven’t caught anyone, right? You haven’t found the shooter?’ Leo isn’t looking at her, nor is he raising his voice, but curled up deep inside his question, Nolwazi recognises it – the anger.

‘No,’ she says, ‘but we will.’

He doesn’t respond.

‘Okay, gentlemen,’ she tries again, ‘one last thing: have either of you thought about why an unknown man would stop and shoot Benjamin for no reason at all? Is there anyone that we don’t know about who would have wanted to hurt him?’

They are both silent for a moment, before Eric says, ‘No.’

Leo says, ‘It’s all people could talk about, for months and months. All anyone on campus wanted to talk about. What happened to him and why. People were scared, I think. And worried. And they like gossip, too. And Freya disappeared. We haven’t seen her since, not once. She vanished. And you’re only asking this question now.’

‘Actually, Steve says he saw Freya the other night. She was out with that trampy chick Vicky.’ In the wake of their words something seems to pass between them, something invisible and private.

‘Who is Steve?’ she asks.

‘Just a guy who lives in the building. We only kind of know him.’

Nolwazi gets up to leave. ‘Did Ben have a girlfriend, someone else I could talk to? His Facebook page mentions he’s in a relationship, but not with who.’

Eric Evans stares at her for a second before replying, ‘No, I never knew or met Ben’s girlfriend.’

‘Oh, just one more thing, Leo.’

‘Yes?’ he says, his face turned away.

‘Is that your Atos parked out front?’

‘Um, yes. Why?’

‘And Freya Rust, she’s seen that car. She knows it’s yours?’

‘Yes, yes, what’s all this about?’

Nolwazi smiles. ‘Thanks. I’ll let myself out.’

7

‘I thought you said the raid was tomorrow, friend?’

‘Bossman, it is. It is.’

‘Then why is there a fucking pig outside my guy’s place?’

‘I don’t know, bossman.’

‘Find out.’

Slick watches the police car pull away.

Then he stands up straight, throws the hoody back and takes off the beany. It stinks. All clear, he types, leaning against the Atos.

‘You sure your friend with the tattoo doesn’t know anything?’ Slick asks Steve five minutes later, checking the rear-view mirror.

‘Yes, he knows nothing, I promise.’

‘Right, well. Let’s get this stuff back to the house. And then I want you to tell me why there is so much product left. You’re not selling fast enough. I didn’t promote you just so you could slack off.’

‘It’s not like you’re paying me more,’ Steve mutters.

Slick slaps him across the face, and his lip splits open; Steve whimpers. ‘Already forgot what happened to the last guy?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Fucking moegoe.’

8

Freya Rust is wearing an oversized jersey and white pyjama bottoms. She has folded herself into a chair in her small living room, and she watches Nolwazi over her bended knee. She has bags under her eyes, but she is looking at Nolwazi intently, as if seeing her for the first time.

‘I spoke to your friends, Ms Rust. They say you haven’t been allowing them to see you.’

‘Call me Freya,’ she says, lighting a cigarette; grey smoke floats upwards, hovering above their heads. Nolwazi tries not to cough. And Freya says, ‘Which friends?’

‘Alex and Adam.’

‘Alex and Adam just want me to talk to them about Ben. I don’t want to talk about Ben.’

‘And Eric?’

Freya tilts her head sideways slowly, before saying, ‘Eric was just . . . a fling. He was Ben’s friend, really. We were just fooling around.’

‘It seems to me like your brother and Eric were very close.’

‘Sure. Maybe.’

‘Why didn’t you tell us they knew each other?’

‘Is that an important detail?’

‘Everything is important.’

‘Well, I’m not interested in them. Or their grief. I’m only interested in who killed my brother.’

‘You’re not interested in why that man killed your brother?’

‘It’s enough to know that he did it. Reasons won’t change anything.’

‘You’re not interested?�

�

The young woman unfolds herself from the chair and sits forward. ‘Why are you talking to all these other people? Why aren’t you trying to find the man in the red car? The shooter?’

‘We’re finding it very difficult to track down that car or the man who owns it.’

Freya’s cigarette sits idling in the empty paint tin she is using as an ashtray. She says, ‘I think you’re probably not looking hard enough.’

The flat is dirty. The kitchen floor is grimy, and dishes are piled high in the sink. The living room is littered with boxes, filled with half-eaten food. There is a layer of dust over everything, so that Nolwazi can see the girl’s footprints leading from the front door to her bedroom. The air is heavy; the curtains are drawn, casting a darkly yellow glow over the space.

‘Let me ask you something,’ Freya continues, ‘if you do find the man in the red car, if you do manage to track him down, what happens then?’

‘Well,’ Nolwazi says cautiously, ‘we bring him in for questioning. Find his gun, process his car for evidence.’

‘What if you don’t find any?’

‘If he is guilty, we will.’

‘If . . . So what you’re saying is, it’s my word against his?’

‘I’m saying we have to find him before we worry about anything else.’

Freya Rust narrows her eyes, and eases her head back, resting it against the seat of the chair and breathing deeply. She is muttering something to herself, and when she looks back at Nolwazi, she seems flushed, angry.

Nolwazi’s phone rings, and she only answers to give Freya Rust a moment to collect herself. ‘Mngadi?’

‘I just want to give you a heads up on the drugs on Mills Street.’

‘Yes?’

‘There’s a scheduled raid tomorrow.’

‘So it’s being taken care of?’

‘Yup.’

‘Good.’ She kills the call.

‘Who was that?’ Freya asks, with something akin to mockery in her voice.

‘A friend in the drug squad. Police stuff.’

‘Police stuff?’ In Freya’s mouth the words seem churlish, coated with contempt. ‘Police. Stuff. Tell me something – do you like being a police officer?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why?’

The question startles Nolwazi; the answer appears on the tip of her tongue like an actor being called to the stage:

My father was a very violent man. He beat my mom. Me too, but mostly her. He always stopped before it became too serious, before he did permanent damage. But then, there was one night when something changed in him and he couldn’t stop himself, and we had to call an ambulance. When the police showed up, there was a detective with them who came and took our statements. A very tall, very kind woman. She was tough and smart and completely in control of both my parents. This woman managed to make my father’s head bow in shame with just her words. I wanted to be exactly like that detective.

She could tell Freya Rust this story, bond with her, create trust between them. But she isn’t interested in answering this question, this time. She doesn’t want to. So instead she says, ‘Because it pays well,’ and the irony in her voice surprises even her.

Nolwazi decides to clean a little. To give herself a reason to stay. To show some sort of kindness. Give and take. ‘Do you have any gloves?’ she asks.

The girl motions to the cupboard under the sink. Inside there is a pair of dish gloves, still preserved in plastic. They look like the kind a television serial killer would use. Bulky and easy to wash. Neon yellow. So yellow that against the monochrome kitchen colours they don’t seem entirely real, like hands from some other, stranger place, floating in front of her, dangerous and unpredictable. There is silence while she washes the dishes. The sun is bright in the sky and the windows above the sink are submerged in light; she cannot look too closely at them without red dots appearing before her eyes. After a few minutes, the rhythm of the chore allows her to forget where she is.

Until a question comes out of the shadows behind her, quick as silver: ‘So you didn’t do it for justice?’

Nolwazi doesn’t turn around, doesn’t want to look back at the girl, at her folded frame, at her arms crossed against her chest, at the big, dark stain on her jersey.

She says, ‘I don’t think anyone does it for that reason.’

‘Shouldn’t that be your reason? Shouldn’t people become police officers to make sure we live in a good world – a world where bad things don’t happen?’

‘Yes, they should. But that world doesn’t exist.’

‘That’s cynical.’

‘That’s reality. Nothing brings you down to earth as fast as being a police officer.’

Freya Rust is silent after Nolwazi says this, so she begins drying the dishes and putting them away, not looking in the direction of the living room. The kitchen smells like lemon-scented soap and smoke – a sultry, unnatural combination.

Then another question comes from the shadows. ‘Do you know where my name comes from?’

Nolwazi shakes her head.

‘Freya is a Norwegian goddess. The goddess of love. But also the goddess of war and justice. And an angel of vengeance. I never liked my name much. People teased me. But now I like it, I think.’

Nolwazi moves back into the living room, Freya Rust sitting in the middle of it like a collapsing star. She notices two photographs on a side table shoved into a corner of the room. ‘How did your parents die?’ she asks.

Freya’s answer is terse: ‘They died in a car crash.’

‘That’s awful.’

‘Tragic.’ The word comes and lies on the floor between them, an abandoned balloon; Freya steps on it without hesitation: ‘You think that was callous,’ she says.

‘No, I think that was true. That’s a nice photo of your brother.’

Freya doesn’t look at it. ‘It’s a reminder.’

‘A reminder of what?’

‘A reminder to keep on living.’ There is a kind of energy about her; a kind of taut frenzy that is being very carefully controlled.

Nolwazi doesn’t think she can bear another moment in the presence of this girl, so she decides to get to the point. ‘Freya,’ she begins, putting her hand out as if to steady a falling glass, ‘I am going to ask you this only once. Are you sure, positive, that you saw that man pull the trigger on the night your brother died?’

Freya Rust is quiet in the face of this question, unblinking. She lights another cigarette. ‘I think you better leave,’ she says.

‘Your aunt came to see me,’ Nolwazi says now, looking to change the subject.

‘You mean my cousin?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘What did she want?’

‘She’s not happy with the speed of the investigation.’

‘Well, can you blame her?’

‘She also seemed concerned about you. She says she hasn’t seen you since it happened, that you won’t see her, that you aren’t home when she comes by, that you’ve changed your phone number . . . She doesn’t know how you’re surviving.’

‘I’ve got money; I can look after myself.’

‘I don’t think that’s quite what she meant.’

‘Well, I don’t want to see her. She’s not my family. She makes me feel guilty.’ Freya looks down as she says this, and from the shadow she is casting over herself, she continues, ‘You know after my brother died, I phoned the police station every day to find out if there had been any leads. I came there, to check up in person. After a while, you stop wanting to hear that nothing has been found, that nothing has been done.’

The accusation slips out into the unbreathable air and begins orbiting the two of them. Nolwazi stands, desperate to escape this strange, unpredictable conversation. Before she leaves, she can’t help but ask, ‘Are you seeing anyone? A grief counsellor or therapist? Is there anyone who is helping you?’

Freya pauses for a minute, then says with a sardonic laugh, �

�Yes, there is. His name is Abraham. He’s really helping me cope.’

Tuesday

9

She’s home.

The smoke, greyer than the sky above it, hangs low and stagnant over the shacks. From Nolwazi’s vantage point on the edge of the township – behind her a copse of blue-gum trees, ahead of her a storm of shacks charging the horizon – she can see the white roof of the police station. It towers above everything around it because it is the only permanent structure visible. There was a day in the not-too-distant past when the police station was on the edge of Mamelodi, but over the past few years it has been swallowed by the rapid growth of poverty. Now it’s surrounded by shacks: tin and cardboard and feeble. Hopeless.

Pretoria has roots – deep concrete roots that bind the city to the earth with steel and mortar, permanent, immutable. There are parts of Mamelodi that are like this, that are stable and strong – roads and schools and clinics and running water. Actual houses fixed to the ground; not the kind of house you can carry on your back, like the ones in front of her now, which quiver like pieces of grass trying to grow in the sand. Shifting, battered; set to blow away at any moment. She eyes the row of temporary toilets to her left – she’s trying to keep them out of her field of vision. Something about them – something about how plastic and corporate they are – unnerves her, scratches something inside her she’d rather not have scratched.

Her hazards are flashing behind her in the grim afternoon light, which gives the corrugated-iron houses an odd glow.

On the edge of the township, there is sparse veld and thorny shrubbery swimming in muddy rubbish. Blues and reds and yellows adorn the ground, calling out brand names, claiming their part in this ugly corner of the world.

She watches an old woman hobble towards the toilets.

Talion

Talion