- Home

- Beyers de Vos

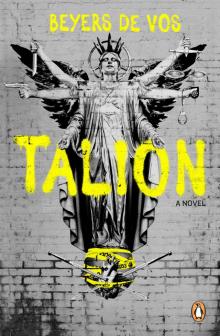

Talion Page 15

Talion Read online

Page 15

‘Boss?’

‘What? Sorry. I got distracted.’

‘What do you want me to do?’

‘Double-check every detail of Freya Rust’s original statement. Go through the files from the armed-robbery case, see if you can find any connections to this one. Focus on the Mercedes. And get a copy of the sketch Freya Rust gave and see if it matches any suspects from back in the day.’

‘There weren’t any suspects.’

‘No one?’

‘Nope.’

‘Well then just the car, thanks. I’ll see you tomorrow.’

‘Sure thing. Unless . . .’

‘Unless what?’

‘Unless you want to meet up later?’

She looks up at the sky. The moon, bright and fierce, is friendlier than those two unconcerned planets, and it stirs something in her. A kind of yearning, a kind of love. Is it possible to be in love with loneliness?

‘Sure,’ she says, ‘my place, one hour.’

29

A crowd is gathering on Abraham’s front lawn. Torches are being tested, final instructions handed out. Pairs of people seem to be moving away in different directions. Freya is watching from the shed. The lights in the back garden have been turned on, and she is glad for her newly discovered hiding place.

Her gun is strapped to her waist with a holster that Greg stole from the shooting range.

The night is scented with ice and straw. Deep winter nights are quieter than other nights: insects vanish; there are no leaves for the soft breezes to rustle, and the grass has been frozen into place. The birds have fled. The silence is starker; the silence is worse. And if following someone by car has turned out to be surprisingly easy, then doing it by foot has turned out to be impossible. Streets, even ones that are badly lit, are never as dark as you would expect; there are no shadows in which to hide in the broad avenues of suburbia. It is also nearly impossible to muffle the sounds of footsteps.

But tonight is different. Tonight, the wind is howling. Tonight, street lamps have been switched off to conserve power; the whole neighbourhood has been thrown into total darkness.

Tonight is perfect.

Know when the animal is vulnerable; know when to strike. Her father’s voice comes into her mind as she quietly steps from the shed, ready to follow Abraham into the night.

30

Slick often thinks about fires. One strike of a match, one strike of lightning, and everything in this dry winter would be burnt away.

His whole empire up in flames.

When he began operating in Hatfield, he spent every night on some street corner, disguised, getting to know the neighbourhood: the students and the industries around them. He became just another bum, offering drugs. He made friends with the other dealers, got to know his customers. He began incorporating people like Bra Joe into his network. He kept himself small enough not to bother the big dealers in the area, and started selling his own-grown product to them at a discount to keep them happy.

And he flourished.

But there is a separate enterprise, in which he plays a smaller part. About a year ago, he began working as a middleman for a bigger organisation: cocaine, which seemed to arrive in Pretoria decades after it did in other middle-class utopias. And crystal meth, the sweet stuff, the stuff of poverty. In these substances he trades only lightly, only for certain clients, only on request, and he is careful which of his lieutenants he lets into this second, darker world. There is a lot of money to be made, but it is a process he doesn’t have complete control over. He dabbles, but cautiously. And he has already been betrayed, more than once.

Betrayal that had deadly consequences for more than one of the boys working for him. Betrayal that he can still feel in the air, a smothering presence.

The doorbell rings.

His friend is at the door, breath fogging up the doorstep. ‘You live seriously close to this chick I’m seeing’s place,’ his friend says, pushing past Slick into the flat and looking around. ‘Why don’t you have any furniture?’

Slick’s eyes flick around his empty flat, the mattress on the floor, the small table with a kettle in the corner. Why no furniture? Because what is the point? He is used to sleeping on the floor. He has few possessions. His iPod. His clothes. The photograph hanging on the wall of his drug room. What else is there? How is he supposed to fill up the house? What is he supposed to put in it? He doesn’t understand what other people fill their homes with; what do they do with all that space?

But he ignores the question. ‘Do you have what I asked for?’

‘Ja, here.’ His friend hands him a file. ‘Everything I could find on Abraham October. Bossman, should we be worried about this teacher? Does he know anything?’

‘He might.’

‘Are you going to kill him?’

‘Maybe.’

‘He’s a bad target, bossman. Teacher, elder in the church. He’ll be missed. And the investigation won’t come my way. It will go to Sunnyside. I can’t protect you.’

‘Thanks for the advice. Get out.’

When his friend is gone, he puts the file down carefully and sits watching the darkness. He looks at the photograph, no longer in its glass frame, lying next to him on the thin mattress. He stole it from the desk in her room, on the night she vanished. On the night the men came into the house and told them all to leave – told them that her reign was over.

He had to flee. Flee again. But he managed to salvage that one photograph of her.

The woman in the photograph stares back impassively, mysteriously.

Mama Africa.

She had no discernible nationality. Her skin was white, but heavily made up, so that it looked bleached and false. Her head was always wrapped in cloth of various patterns – sometimes Chinese, woven from silken gold. Sometimes African, the colours of the earth. Sometimes Indian, bright and bristling. Her eyes were dark, and they had a slight Asian lilt, a bent that spoke of exoticisms, but she lined them in thick dark curves, so that it was difficult for a child who had never seen anyone who didn’t look like him to tell the shape of her eyes. She was also fond of tinted contact lenses, so that he would for ever think of her eyes as green because that’s the colour they were the first time he saw her. But they became other colours, other people, on other days. She was of all cultures, and no cultures. It was the perfect disguise – impregnable, intimidating, insulating – and in the time that Slick knew her she spoke at least six languages fluently, perfectly. Never in the entire time he was in her service did he have the courage to ask her where she came from. ‘Do you know what “erudite” means?’ Mama Africa asked him not long after she met him, in Zulu, although it seemed impossible, alien, that she could speak this language. The English word perched on the Zulu sentence like an alien thing, a glossy parasite riding her tongue.

He spent a long time, when he was younger, thinking about Mama Africa’s tongue. It was little and sharp and very, unusually, pink.

It was she who taught him English, and when he speaks it now, he still hears her voice come from his lips; he doesn’t sound like himself, doesn’t recognise the round, blue sounds that tumble from him like poisonous berries. It feels wrong, weak. His own language is strong and muscular, warm-blooded and assured. But when he speaks English, his tongue has to slide when it wants to click, snake when it wants to fly. His English is distracting even to his own ears, but he likes (oh, he likes very much) the way it puts other people off – so he practises it and polishes it like a weapon. Another skill to put in his arsenal of disguises.

She was also the one who christened him Slick: a new name, better than his old name.

He looks away from Mama Africa.

The memories he has of the time between running away from home and being found by Mama Africa are red-and-black chaos. The feral bleakness of living from moment to moment, night to night, losing his humanity, losing his language. Writhing, pure emotion. No, not emotion. Instinct. It was like his brain forgot how to process

memory, how to build his experience into something solid or functional.

She found him, and he still doesn’t know how: where she heard that there was a boy sleeping in that abandoned building. But she probably saved his life. Mama Africa saved many lives this way – finding scavenging, homeless, forgotten children from the street and employing them.

Mama Africa, the most powerful drug lord in town. Another thing he only found out later.

So the photograph is the one thing he has: the one thing he would save, if the world went up in smoke, if the house came crumbling down in a fire.

He looks down at the file in his hand, at the small black-and-white photograph of the teacher staring out at the world: fine-boned, oblivious.

Of course, sooner or later, the teacher is going to have to come crumbling down, too.

31

Freya is in the shadow of a tree, out of sight. She is waiting.

Abraham has been standing at the wall of the house – large and yellow – for over an hour, watching. She has no idea what he could possibly be doing, what he could possibly be waiting for. He should be patrolling; instead, after only twenty minutes, he came to rest here, on this out-of-the-way street, attentively watching.

Freya is getting nervous of being seen or heard.

But for some reason she can’t bring herself to move, to walk back the way they came. She isn’t even sure she could find her way back without him.

She sneaks a glance from behind the tree. He is still standing in the street, a hard, thoughtful look on his face. What is he doing? Why is he just standing there? Is he waiting for something? She fingers the gun at her side, the weight of it still novel, still unbalancing her. A thought materialises on the shore of her mind – a miraculous thought that has been taking shape for a week – and this time she allows it to solidify; she doesn’t let it slip like rain through a gutter. She picks up her gun, releasing it from its holster without a sound. She raises it. She breathes in.

She aims.

She holds her breath.

Could it be over this easily? Is she really about to shoot Abraham October? She can feel the soft barrier between life and death bulging outwards, the membrane threatening to burst, and she can sense, like a faint and frenzied whisper, the sound of a world in which Abraham October is dead. A world in which her brother has been avenged.

Her breath clouds up the night air, white wisps of uncertainty.

But then, from behind her, an unnatural sound. A scratching. She lowers the weapon and frowns. It’s an odd sound, and has an abnormal rhythm to it, a slippage at the end of each beat. Freya holds her breath, and slowly moves her head back behind the tree. She turns around, her back now on Abraham. She teases her finger away from the trigger. The road is wide, surrounded by gardens and front lawns that are hidden in darkness. The street lamps aren’t lit because the power outage is still in effect. Anybody could be hiding anywhere. She listens intently. The scratching noise sounds like it is close by, like it is coming closer. She can hear her breathing becoming laboured: heavy, beginning to panic. Then she realises what it is – it’s the sound of fabric rubbing together, of one leg brushing up against the other.

It’s the sound of someone coming towards her.

32

He stands at the edge of the garden, outside of the light.

His daughter is sitting at a dining-room table, laughing. Like she’s in a photograph. She is talking to someone outside of the frame. Mr October hasn’t seen her smile in a long time.

She’s been avoiding her usual hangouts. Following her has become difficult.

But at least he knows where she is on weeknights. Here, at this house. Enclosed in this warm glow. This was his private reason for starting the neighbourhood watch, for agreeing to patrol the streets. So he could come stand here, in these shadows, and watch his daughter join the warmth and comfort of another family.

Mr October, the spectator.

Mr October, the absent father.

Mr October. He doesn’t know when he started thinking about himself like this. It’s been so long since he’s been anyone else. So long since he’s been Pa. Or Husband. Or Abraham.

All he hears these days is Mr October.

33

The sound has stopped. Just as quickly as it started. But now Freya cannot help feeling that someone is lurking just inside the distant shadows – that someone else is here, in the street, camouflaged just as she is. A ghost. A ghost.

If it were another member of the neighbourhood watch, surely they would show themselves?

It takes a great effort of will for her to turn around, to turn her back on the street, and chance another look at Abraham.

But he is nowhere to be seen. The spot where he was standing moments ago is empty. Which way would he have gone? Further down the street or back the way they came? She begins moving again, walking fast this time, trying to catch up with him, choosing a direction at random. She’s been distracted. He’s led her into a part of the neighbourhood she’s never been to before. A rougher part of it, nearer the train station; she doesn’t recognise these streets.

As soon as she starts walking, the scratching sound starts up again.

Why are all these roads so curved, so intertwined?

This was a bad idea, this whole last week. Why had she decided to follow him? What had been her real reason? What had she been planning on doing? It is stupid; this whole thing is stupid. She should have gone to the police when she first found him. She should hand him over. This daze she’s been in, this other reality, it’s consuming her. It’s an addiction, a disease. She needs to stop it. She sees that now. Stop this and hand Abraham to the police and let justice run its natural course.

She isn’t some avenging angel.

Then the silence breaks like ice; an owl screeches somewhere nearby. A bird-shadow rises from behind a wall to her left and struggles into flight.

And as Freya jumps back, startled by the sound, something heavy and solid comes out of the darkness behind her.

And catches hold of her.

Without thought, without will, Freya begins to scream.

34

Mr October is standing inside his shed, staring at The Creatures. Little hauntlings that have buried into his consciousness, activated his memories. All this reminiscing, all these old wounds, triggered by Sara’s death. By grief. Grief, like a mythical box that unleashes into the world anger and desperation and paralysis, violence and hatefulness.

How is it possible that a life could become so eroded?

Nothing is ever going to change again, not for him. Life has reached stasis. Terrible, cold stasis. He’s been spending the past year wandering through the routine of his empty existence, picking up memories and shaking them loose, watching them disintegrate and diminish under the assault of time. What does the future look like? What happens in a few months when his daughter leaves – and she will leave, of that he is sure. Will this be it? This blighted nothingness, living alongside the echoes of the things that have been taken from him, the things he couldn’t control. The plastic heads of plastic babies, spectres of his wife’s mind, hanging in this shed; the shed he built with his bare hands.

This is his punishment for leaving that young man for dead, he knows. And for abandoning Sara to the forces of her own mind. He deserves this. He has to live with it. He won’t choose the path his wife took: chemical numbing, slow suicide. He won’t indulge that kind of self-mercy. This is his punishment and he will take it like a man, like a man of God. But he will make sure the one thing he has left – the one legacy he can still leave – makes an impact on the world that is good. That from all the damage done there can come some kindness: the hope at the bottom of the box. The time of silence is over; he needs to talk to his daughter. He needs to fix this one thing, this last thing. If he can.

The faded sepia photograph is too big for the frame; the bottom edge is frayed and crumpled. It shows two people standing side by side outside a church, holding hands.

They look like something from another era: almost twenty years ago now. Lifetimes. He wore an old brown suit that his father had left behind and she wore her mother’s wedding dress. It had a tear in the train and had yellowed slightly, but it hardly mattered. They had not been dating for long, but they were happy enough. Besides, she was pregnant. The wedding was short, frugal, and festive. There were homemade lanterns in the tree overlooking the tiny, dusty yard. Sara had white daisies in her hair. Her uncle’s accordion band was playing in the corner, the hooting, jangling music mingling with deep and sincere laughter. And there was, at least, a little space for dancing.

The wedding night was frenzied and joyful.

It was the beginning, the end.

He hears the soft tread of a footfall behind him, and turns.

That same note of accusation is in her voice now as it is every time she speaks to him, the same barbed wire in her eyes. She pushes past him, grabbing the photo. ‘Where did you get this?’ she asks.

‘In Ma’s old stuff.’

‘You said all the photos of her were gone.’

‘I lied.’

The hurt rippling across her face doesn’t surprise him, but that is when he notices the residue of tears on her cheeks, sweat dripping from her brow, the streak of wet hair sticking to her skin. She is panting softly; her dress is dishevelled. ‘What’s wrong? What’s happened?’ he asks. She is looking down at the photograph, and he doesn’t expect her to answer. He expects that she will retreat into secrecy, into silence once more.

But then she says, ‘You have to come.’

Talion

Talion